The appendix is a small out-pouching off a part of the large intestine known as the cecum. It functions similar to normal large intestine by secreting mucous and absorbing water. Its overall importance, however, is not well understood, and it is likely a vestigial remnant from a distant ancestor. Unfortunately for some unlucky folk it can become inflamed; when this occurs it is called “appendicitis”.

Appendicitis occurs when something blocks the opening of the appendix into the cecum. There are numerous causes. The most common in younger individuals is a mass of inflammatory cells known as lymphoid hyperplasia, which can occur after a viral or bacterial infection of the gut. In older individuals, the most common cause is a small, hard piece of poop known as a “fecalith”.

When lymphoid hyperplasia or a fecalith (or any other obstructing thing) blocks the opening of the appendix, any mucous secreted by it gets trapped. When the appendix becomes distended enough, it literally chokes off its own blood supply and starts to die.

The dying appendix sets off a cascade of inflammation. Bacteria within the intestine are able to move in and wreak further havoc! The end result is a nasty inflammatory process, that if left unchecked, can lead to a very serious surgical illness.

Signs and Symptoms

Appendicitis initially presents with periumbilical pain (ie: pain around the belly button) that quickly migrates to involve the right lower quadrant of the abdomen.

The reason pain occurs in this sequence is because the initial discomfort of appendicitis is due to inflammation of the visceral peritoneum and appendix itself. The visceral peritoneum is a layer of tissue that envelopes the gut tube. This type of pain is carried back to the spinal cord by autonomic nerves, and due to their embryological origin, that pain gets referred to the midline of the abdomen (the belly button).

Over the course of the disease, the parietal peritoneum eventually becomes inflamed. This pain is carried by somatosensory nerves with a very specific dermatomal distribution, thus the pain gets localized directly to the anatomical location of the appendix – the right lower quadrant. This pain is often very well localized at an area known as McBurney’s point.

Patients often have nausea, vomiting, and a decreased appetite. In fact, if patients are hungry and want to eat, appendicitis becomes a highly unlikely diagnosis for abdominal pain. This is referred to informally as the "cheeseburger sign".

There are also several physical exam findings. Pain with palpation of the right lower quadrant associated with rebound tenderness (ie: pain that occurs when you release pressure during palpation) is frequently seen. Sometimes palpating the left lower quadrant (ie: the area on the other side of the abdomen from the appendix) will cause discomfort in the right lower quadrant. This is known as "Rovsing’s sign".

Any maneuvers that irritate the peritoneum will also cause discomfort. The first of these signs occurs when you flex the hip. This causes the iliopsoas muscle to rub up against an inflamed peritoneum. This is known as the "psoas sign". Another way to irritate the peritoneum is to internally rotate the leg while the patient’s knee and hip are flexed. This is known as the "obturator sign".

Diagnosis

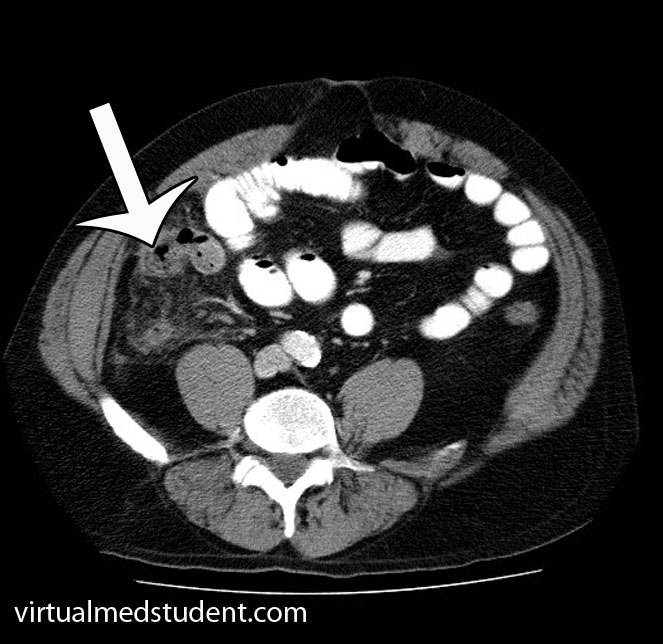

However, in a world with advanced imaging technologies we can quickly get pictures that support the diagnosis. Both ultrasound (frequently used in children, pregnant patients, and younger adults) or CT scans can be obtained quickly and inexpensively. The CT scan will show fat stranding and fluid around an enlarged appendix (see image to the left).

Blood tests such as a complete blood count (CBC) will show an elevated white blood cell count (ie: the cells that fight off infection and are responsible for inflammation).

Treatment

Treatment is surgical (ie: appendectomy)! Get that nasty inflamed appendix out of there STAT! In addition, patients are started on intravenous fluids and antibiotics that cover anaerobic organisms.

Commonly used antibiotics for a non-ruptured appendix are metronidazole, ampicillin/sulbactam, and ciprofloxacin. If the appendix has ruptured, broad spectrum coverage with piperacillin/tazobactam or a combination of ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, and clindamycin is started and continued for at least 5 days.

Occasionally a ruptured appendix will wall itself off into an abscess. If this is the case, the abscess must be drained with a needle. Antibiotics are started, and the patient is taken to surgery roughly six weeks later to remove the appendix after the inflammation has "calmed down".

Overview

Appendicitis occurs when something blocks the opening of the appendix into the cecum. Progressive enlargement of the appendix occurs eventually chocking off its own blood supply. Pain in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen is a common symptom of appendicitis. Diagnosis is clinical, but ultrasound and CT scanning can be helpful in elucidating unclear cases. Treatment is appendectomy (removal of the appendix), IV fluids, and antibiotics.

References and Resources

- Merlin MA, Shah CN, Shiroff AM. Evidence-based appendicitis: the initial work-up. Postgrad Med. 2010 May;122(3):189-95.

- Kim JK, Ryoo S, Oh HK, et al. Management of appendicitis presenting with abscess or mass. J Korean Soc Coloproctology. 2010 Dec;26(6):413-9. Epub 2010 Dec 31.

- Lee SL, Islam S, Cassidy LD. Antibiotics and appendicitis in the pediatric population: an American Pediatric Surgical Association Outcomes and Clinical Trials Committee systematic review. J Pediatr Surg. 2010 Nov;45(11):2181-5.

- Markides G, Subar D, Riyad K. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in adults with complicated appendicitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2010 Sep;34(9):2026-40.

- Grundmann RT, Petersen M, Lippert H, et al. The acute (surgical) abdomen – epidemiology, diagnosis and general principles of management. Z Gastroenterol. 2010 Jun;48(6):696-706. Epub 2010 Jun 1.